He was born on October 2, 1918, in Portland, Maine in the United States. Like many men in the U.S. military in the early 1950s, he would die while serving his country halfway around the world in Korea.

Major Charles J. Loring Jr., U.S. Air Force

His service does not begin there. By the time Major Charles J. Loring, Jr. served in Korea as the Operations Officer of the 36th Fighter-Bomber Squadron he was 34 years old. His military story would begin in March of 1942, shortly after the U.S. entered WWII, when he enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps at age 23. In May he became a cadet and after a lengthy training period was commissioned a second lieutenant.

World War II

His pilot career started out in December 1942 flying anti-submarine aircraft based in Puerto Rico. His unit, the 22nd Fighter Squadron of the 36th Fighter Group, was tasked with defending the Caribbean and the Panama Canal. It would be over a year later in April 1944 when the 36th Fighter Group was transferred to England that Loring would make it to the European front. Loring, along with thousands of other pilots, would support the Normandy Invasion. As Operation Overlord commenced, his unit would be involved in reconnaissance, fighter escort, and bombing missions.

They were very busy from D-day on and he had flown 55 combat missions by December 1944. He would receive the Distinguished Flying Cross for destroying ten German armored vehicles in a single mission. Unfortunately, on Christmas Eve of 1944, his P-47 Thunderbolt was hit by flack while he strafed ground targets and he was shot down over Belgium. He would become a POW for six months until his camp was liberated on May 5, 1945.

Between the Wars

Between WWII and the Korean War, Loring would serve in multiple roles across the United States. Stationed in Texas in November 1945, he was a pilot and post exchange officer. In Seattle, Washington he was a public information officer in November 1946. Beginning in November 1948, he became an instructor with the Armed Forces Information School in Pennsylvania.

Korean War

With the breakout of the Korean War, he would soon see himself back in a cockpit flying combat missions. Though the war broke out in June 1950, Loring would not be sent to Korea until February 1952 and later in July was assigned as the Operations Officer of the 36th Fighter-Bomber Squadron. In this aerial combat unit, he would be a pilot in an F-80 Shooting Star.

A U.S. Air Force Lockheed P-80A-1-LO Shooting Star

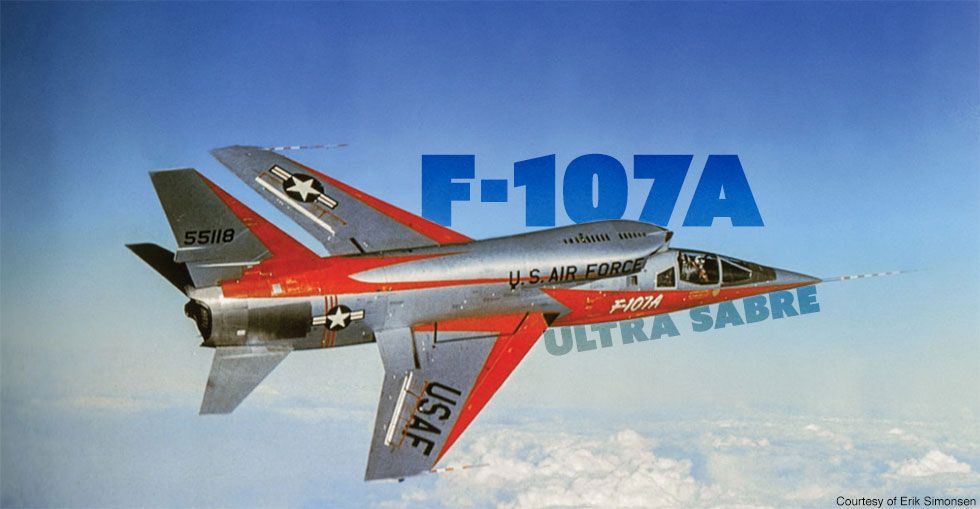

P-80 Shooting Star

Introduced into service in 1945, the F-80 was the United States Air Force’s first successful turbojet-powered fighter aircraft. This jet helped to usher in the jet age. Like the propeller fighters of the 40s, the F-80 was designed with straight wings. The P-80 had a maximum speed of 580 mph, a rate of climb of 5,000 ft/min, and a range of 790 miles. It was one of the first jets to be in service with ejection seats. Despite its seemingly impressive speed for its time, it competed in Korea with the MiG-15, which was a swept-wing aircraft. The MiG-15 had a higher top speed of 670 mph and was superior to the Shooting Star in nearly all categories. The entry of the MiG-15 into the war meant the days of the P-80 as a dogfighter were over. It would soon be replaced by the F-86 Sabre, America’s first swept-wing fighter that turned the tide of the air battle back to the U.S.

Also Read: Jet Friday: F-86 Sabre – Dogfight over Korea

Attacking Triangle Hill

In his P-80 Shooting Star, Major Charles Loring’s unit was primarily responsible for close-air support and airstrikes. By November of 1952, Loring has reached 50 combat missions.

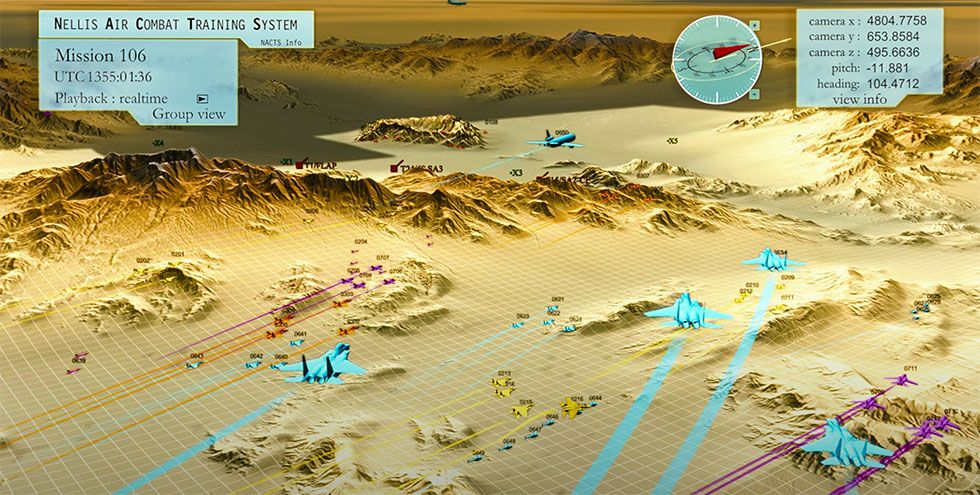

During the month of November, NATO troops were targeting a key concentration of Chinese and North Korean troops and artillery. On November 22, NATO forces were pinned down in an area known as Triangle Hill and Sniper Ridge. The Chinese had established large-caliber guns, rocket launchers, and anti-aircraft guns along these ridgelines and were targeting NATO troops. Ground troops were unable to reach the big guns because they were heavily guarded.

That day Major Charles Loring was the leader of a four-plane flight of F-80 Shooting Stars. While on a ground support mission, Loring was briefed about the heavy guns and ground troops’ situation. His flight diverted to dive-bomb the enemy gun positions. As he located the heavy guns and lined up to dive onto the targets, his aircraft was exposed to extremely precise anti-aircraft fire. Despite his aircraft becoming heavily damaged he did not pull out of his dive. He could have withdrawn back to his base or even ejected but chose neither. His prior experience in WWII likely led him to avoid becoming a Chinese POW. His wingmen observed Loring deliberately turn his aircraft 40 degrees and in controlled flight drove his aircraft into the heavy gun emplacements taking them out. He would not survive the crash.

Medal of Honor

Loring was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor. Loring Air Force Base in Maine would be named in his honor. His Medal of Honor Citation reads:

Major CHARLES J LORING, JR., distinguished himself by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty as a Pilot with the 8th Fighter Bomber Wing, Fifth Air Force, on 22 November 1952. On that date, Major LORING was leading a flight of four F-80 type aircraft on a close support mission near Sniper Ridge, North Korea. The flight was briefed by a Mosquito controller to dive bomb enemy gun positions along the ridge which were harassing friendly ground troops. After verbally verifying the location of the target by a radio transmission, Major LORING rolled into his dive bomb run. Extremely accurate ground fire was directed on Major LORING’s aircraft throughout the long run. However, disregarding the accuracy and intensity of flak concentrated around his aircraft, Major LORING continued to aggressively press his attack, until he was hit by ground fire at approximately four thousand feet. At this point, Major LORING deliberately altered his course and aimed his diving aircraft at active gun emplacements on a ridge northwest of the briefed target. With infinite personal courage and daring, Major LORING elected this sacrifice, turning approximately forty-five degrees to the left and pulling up slightly in a deliberate, controlled maneuver which carried his aircraft directly into the midst of the gun emplacements, destroying them completely. Major LORING’s superlative gallantry and valor far beyond the normal call of duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service, and reflected great credit upon himself, the Far East Air Forces, and the United States Air Force.