It’s 0525 in the morning in north-eastern Afghanistan. There is thick, low cloud coverage over the Korangal Valley, blocking out all light from the moon and stars. Two Marines sit in a listening post about a klick from their firebase. Beneath the thick canopy of pines, the humidity is trapped down on top of them, turning their hastily dug fighting hole into a sauna.

It’s so quiet neither Marine can sleep – they both sense something is up. Animals, birds, bugs–everything is still and silent, like they are on alert themselves. It’s so dark that the Marines cannot see each other sitting in the same hole, so they squat behind a low berm, their eyes closed, heads slowly swiveling so they can focus their sense of hearing on their surroundings.

The silence is broken by the snap of a twig at their 10 o’clock. The sound is deafening, and the Marines flinch. They feel like whatever made the sound surely heard their spines clinch.

Silence again.

Its the longest minute of their lives until the silence is broken by the sound of legs slipping through knee-high grass only five meters from their hole as eight or nine individuals sweep by. One of the bodies whispers commands in Pashto, the language of this Pashtun mountainous region. With no other known patrols in their area, the two Marines recognize this group is very likely a Taliban patrol.

To avoid giving away their position, the Marines hold one minute before they communicate the location of the enemy patrol. The Marine reaches for the knob on his radio and he twists it to turn it on. At first, he doesn’t hear a thing and he gets a sinking feeling. Is the radio dead? Is it malfunctioning because of their crawl to the position? Has the electrical component inside experienced a failure because of the heat and humidity? Or, is the battery dead? How would they warn the firebase?

He turns the knob a little further, just in time to hear some chatter in his earbud. A smile crosses his face as he keys the mic. A patrol soon leaves the firebase to intercept the Taliban patrol.

Experiencing a failure in your military communications at the wrong moment can get someone killed or injured. Redundancy is built into military aviation electronic components to avoid catastrophic failures, but ground communication systems seldom do. Knowing what can cause electronic component failures can help avoid damaging equipment and affecting the mission.

Components with manufacturing defects usually fail within the first few hours. Many manufacturers have a burn-in time to ensure components will fail before they even get to the end user. Interestingly, if a component survives the first few hours, it is likely to survive for a long period of time. The failure curve starts high, drops to near nothing and slowly eases back up over time. Some of the late life causes of failure are listed below.

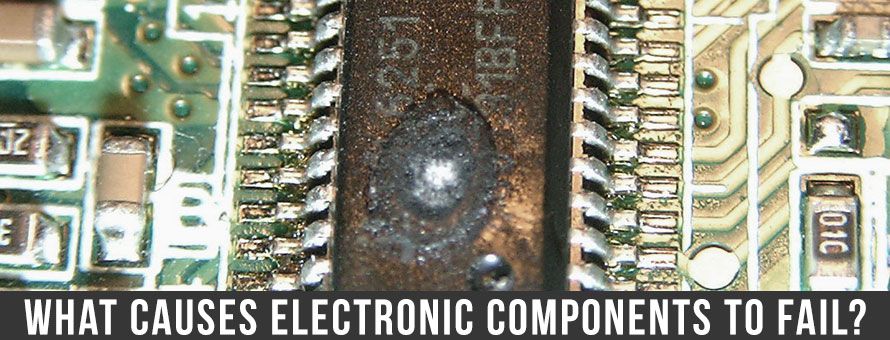

What Causes Electronic Components to Fail?

- Overcurrent or overvoltage: Power surges come from many sources, from lightning strikes to powering off a different piece of equipment on the same power circuit. Engineers put filters in the power supplies to attempt to mediate spikes and surges, but it is impossible to predict the conditions on every line at all times.

- Over temperature: This can be a design flaw or environmental changes, extended operations, or combinations of these factors. Semiconductors are made of differing materials deposited in layers on a substrate. Differing materials will have different expansion rates. Cycling hot and cold repeatedly for a period of time can make these materials separate and fail, or get them hot enough that the materials could even melt!

- Mechanical shock: Have you ever dropped a cell phone? Slamming a piece of equipment against a hard object can jar parts loose or cause them to fracture internally. Add the heat and vibration of a jet engine and that tailhook stop on a carrier can wreck an otherwise healthy component.

- Mechanical stress: Twisting, bouncing, rolling off a ramp–all types of mechanical stresses occur with electronic components. Riding in a tank can treat a radio like it is in a paint can shaker.

- Radiation: Radiation can come in many forms, from nuclear testing to proximity to microwave or radar antennas. Enough radiated power can induce parasitic currents in components and wiring, which may increase voltages or currents beyond the safe design levels in components, ultimately destroying them. Nuclear radiation types and effects are beyond the scope of this article, as it is a very complex, in-depth subject.

- Contamination: Moisture can cause rapid oxidation and corrosion, leading to premature failure. Jet fuel, high detergent hydraulic fluids and lubricants, coatings, spills, and even salty moist air can speed up corrosion and destroy components and wiring.

- Cascading failure: This occurs when a component fails in such a way that it causes conditions which destroy other components around it.

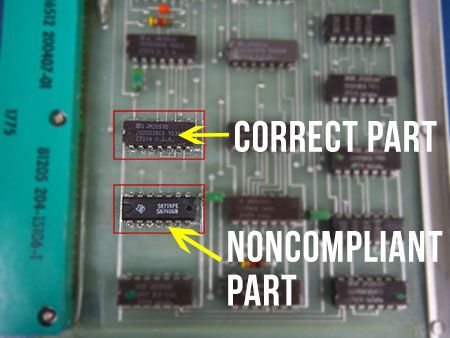

Top: The correct part that has met mil temperature range, testing, screening, quality assurance testing/monitoring and manufacturing facility certifications. Bottom: a noncompliant, but functional, incorrect commercial temperature part installed during a previous repair.

Poor Repair Efforts: When a component is under repair and shortcuts are taken, the component can fail at a later time under normal use. For instance, using a commercial quality circuit versus one that meets the requirements of the assembly places a weak link in the electronic component.

In order to eliminate or reduce electronic component failure, military, maritime, aeronautical electromechanical systems, and space applications must undergo environmental testing based on MIL-STD-810 and DO-160 standards. These standards establish the environmental and other variable conditions under which electronic systems should be operated in during testing.

For instance, a ground-based radio is not only tested for reliability inside a controlled environment like a building but also under the exact conditions that the radio can be expected to operate within when fielded. An operator manages the equipment in conditions that could have very high or low humidity, dusty and sandy, and sees extremely high and low temperatures. This allows for identifying the weak points and addressing them at the design level so equipment can be counted on when the mission calls for it to operate properly.

Repair… Reverse Engineer… Renew

Duotech provides repair support capabilities for base stations, antennas, radar, towers for communications and RF, and also electromechanical and power electronics for ground-based systems.

With over 34 years of experience, DSI provides a full range of equipment repair services. We provide Depot Repair Services for a wide variety of electronic and electromechanical systems for military and commercial applications. We are certified AS9100D and ISO 9001.